Cache

Foreword

Think about it: which part of the server side is most likely to be the first bottleneck when we have a surge in traffic? I believe that most people will encounter is the database first can not carry, the volume up, the database slow query, or even card dead. At this point, the upper service has how strong governance capabilities are not helpful.

So we often say to see a system architecture design is good, many times look at the cache design on how to know. We once encountered such a problem, before I joined, our service is no cache, although the traffic is not high, but every day to the peak traffic period, we will be particularly nervous, down several times a week, the database directly killed, and then nothing can only restart; I was still a consultant, look at the system design, can only save the emergency, let everyone first add the cache, but Due to the lack of knowledge about caching and the confusion of the old system, every business developer would tear the cache according to their own way. This led to the problem that the cache was used, but the data was scattered and there was no way to ensure data consistency. This was indeed a rather painful experience that should resonate with everyone's memories.

I then pushed back the whole system and redesigned it, in which the cache part of the architecture design plays a very obvious role, so I have today's sharing.

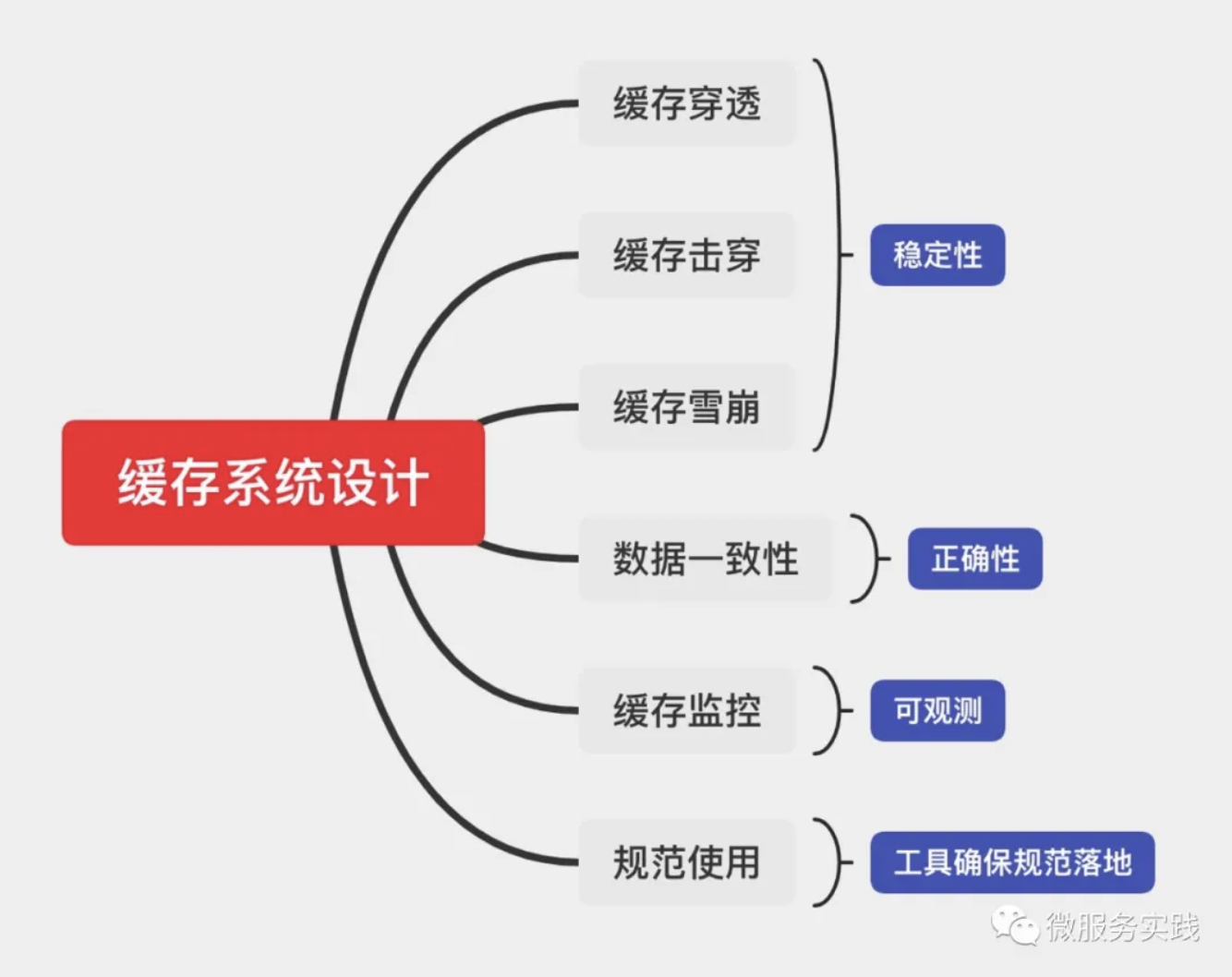

I've divided it into the following sections to discuss with you.

- Caching System FAQ

- Caching and automatic management of single-line queries

- Multi-line query caching mechanism

- Distributed caching system design

- Caching code automation practices

The issues and knowledge involved in caching systems are relatively numerous, and I will discuss them in the following areas.

- Stability

- Correctness

- Observability

- Specification landing and tool building

Cache system stability

In terms of cache stability, basically all cache-related articles and shares on the web will talk about three key points.

- Cache Penetration

- Cache breakdown

- Cache Avalanche

Why talk about cache stability in the first place? You can recall when we introduce caching? Usually, caching is introduced when the DB is under pressure or even frequently hit and hung, so we first introduced the caching system to solve the stability problem.

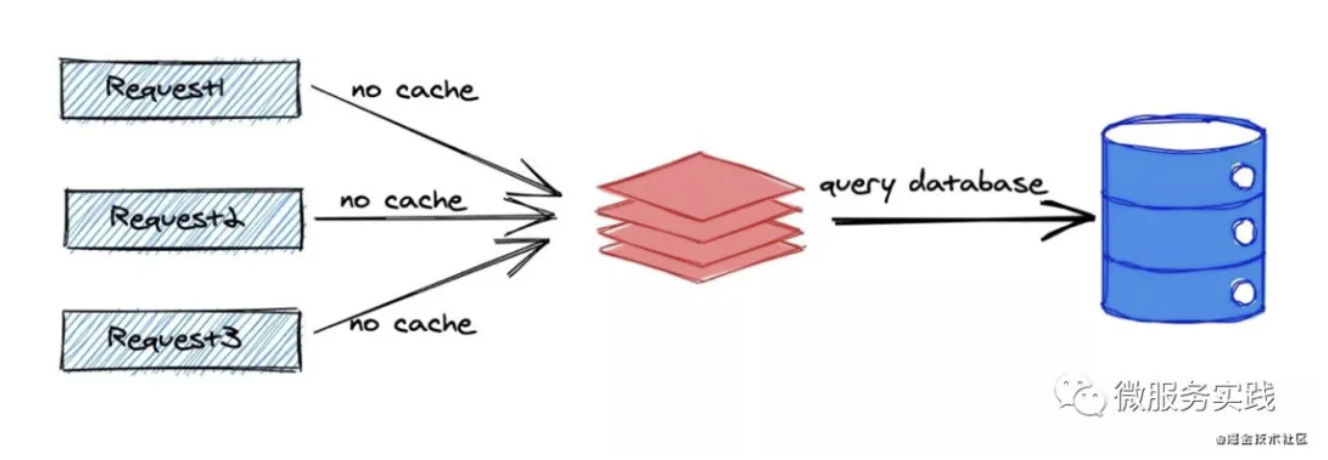

Cache Penetration

Cache penetration exists because the request does not exist data, from the figure we can see that the same data request 1 will go to the cache first, but because the data does not exist, so there is certainly no cache, then it falls to the DB, the same data request 2, request 3 will also fall through the cache to the DB, so when a large number of requests for non-existent data DB pressure will be particularly large, especially may be malicious requests to defeat (unsuspecting people find a data does not exist, and then a large number of requests launched to this non-existent data).

The solution of go-zero is that we also store a placeholder in the cache for non-existent data requests for a short period of time (say one minute), so that the number of DB requests for the same non-existent data will be decoupled from the actual number of requests, and of course the placeholder can be removed on the business side when new data is added to ensure that the new data can be queried immediately.

Cache Breakdown

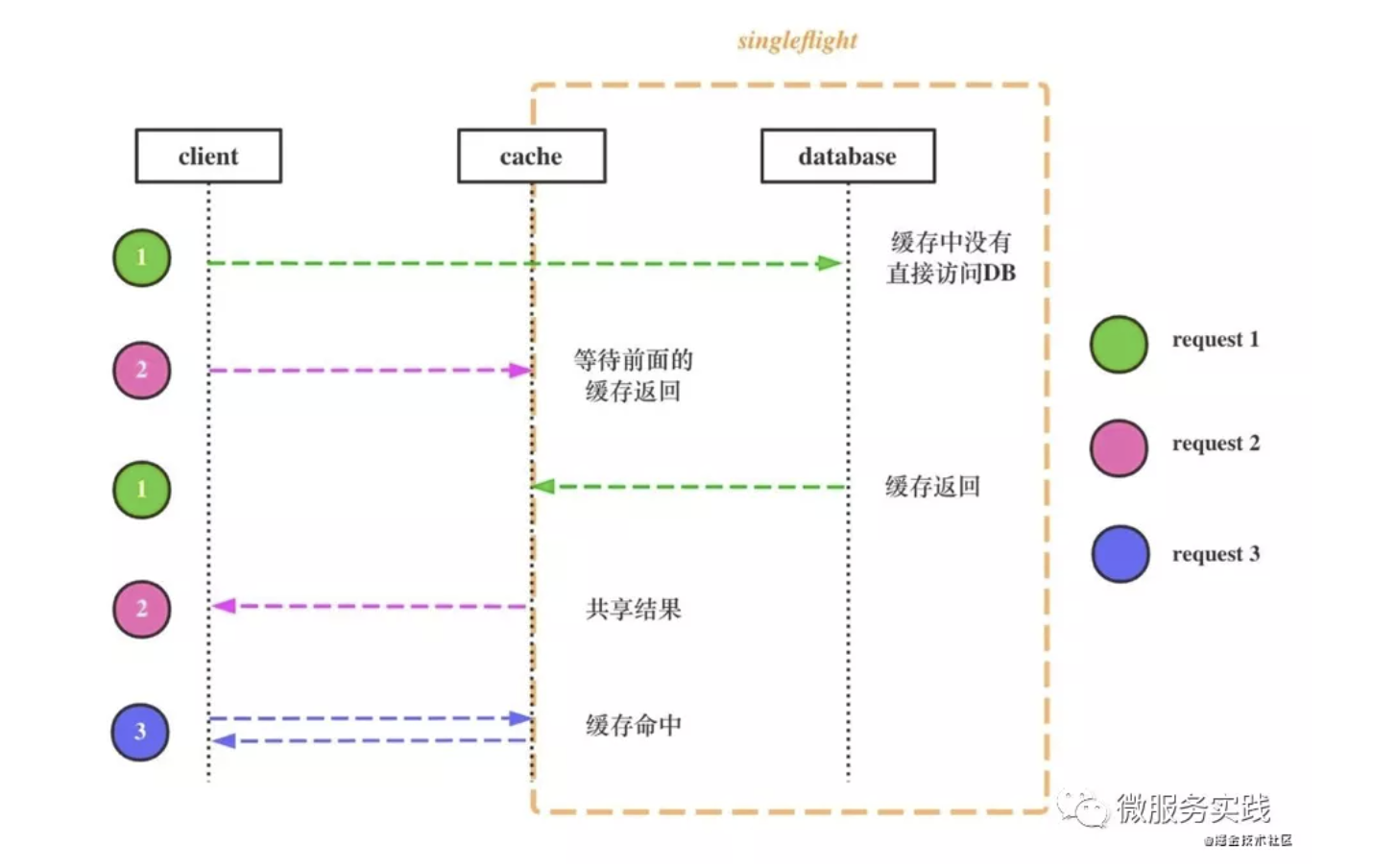

The reason for cache breakdown is the expiration of hot data, because it is hot data, so once it expires, there may be a large number of requests for the hot data at the same time, at this time, if all the requests can not find the data in the cache, if they fall to the DB at the same time, then the DB will be under huge pressure instantly, or even directly stuck.

The solution to go-zero is that for the same data we can rely on core/syncx/SharedCalls to ensure that only one request falls to the DB at the same time, and other requests for the same data wait for the first request to return and share the result or error, depending on the concurrency scenario, we can choose to use in-process locks (not very concurrent) or distributed locks (very concurrent). Very high concurrency), or distributed locks (very high concurrency). After all, introducing distributed locks will increase complexity and cost, drawing on Occam's razor: do not add entities unless necessary.

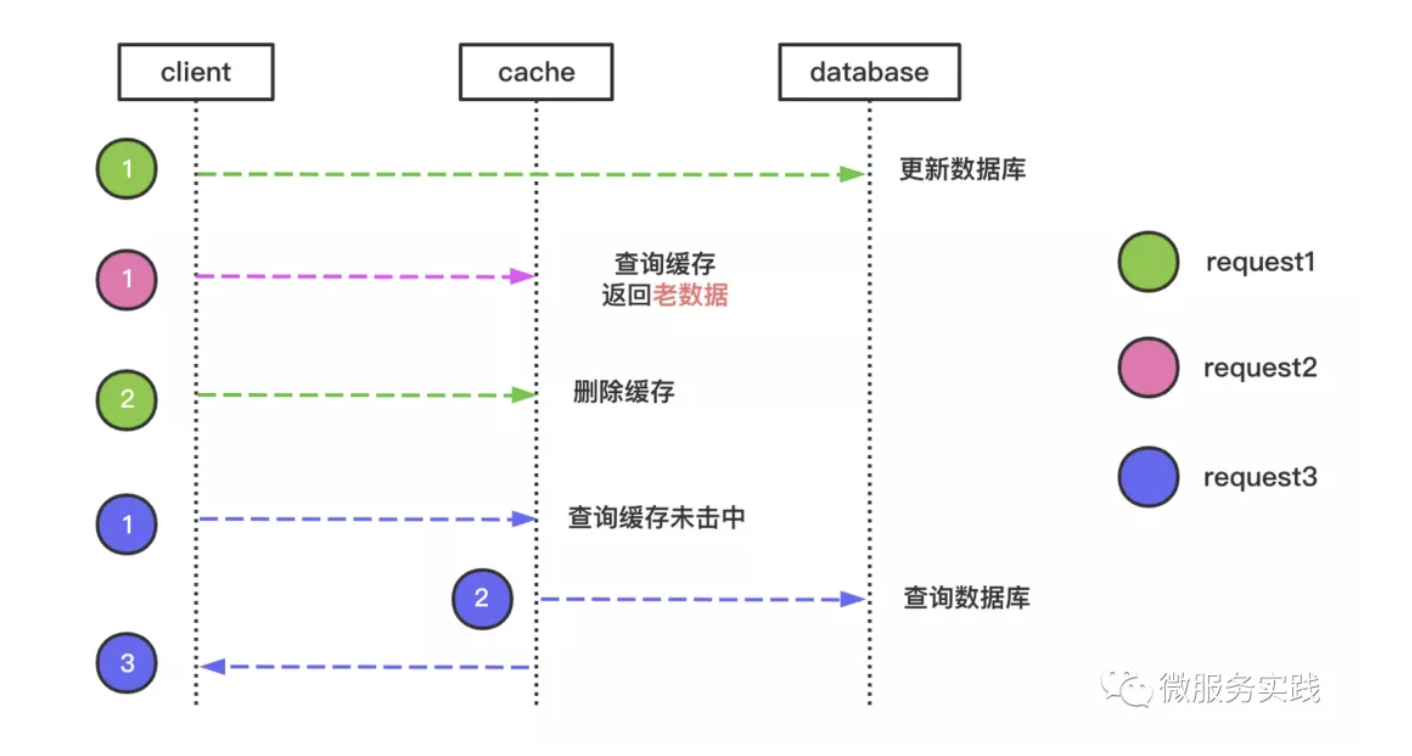

Let's take a look at the cache breakdown protection process together in the figure above, where we use different colors to indicate different requests.

- Green request arrives first, finds no data in the cache, and goes to DB to query

- The pink request arrives, requests the same data, finds that the request is already being processed, and waits for the green request to return, singleflight mode

- The green request returns, the pink request returns with the result shared by the green request

- Subsequent requests, such as blue requests, can get data directly from the cache

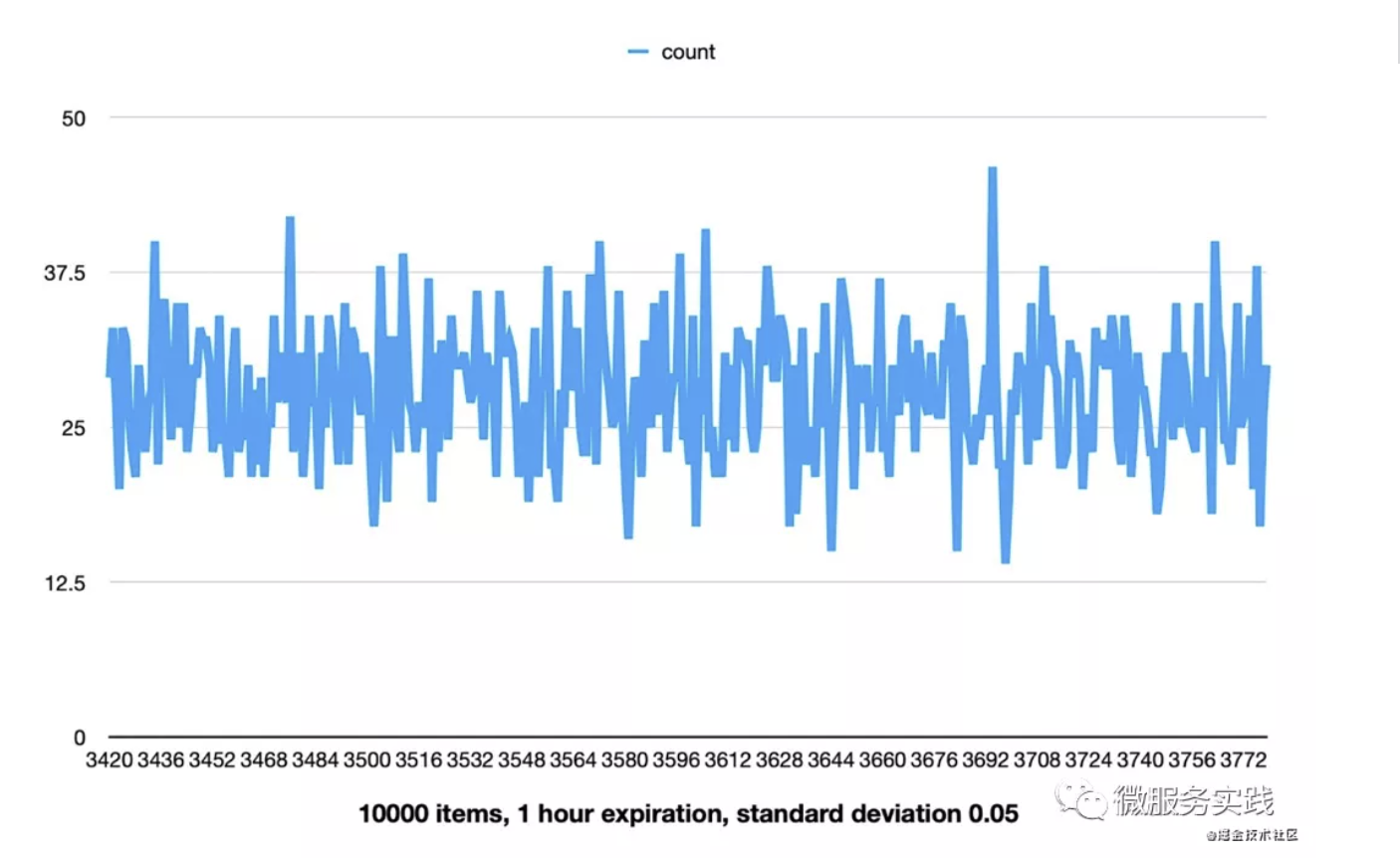

Cache Avalanche

The reason for cache avalanche is that a large number of caches loaded at the same time have the same expiration time, and a large number of caches expire in a short period of time when the expiration time is reached, which will make many requests fall to the DB at the same time, thus causing the DB to spike in pressure and even jam.

For example, in the epidemic online teaching scenario, high school, middle school and elementary school are divided into several time periods to start classes at the same time, then there will be a large amount of data loaded at the same time and the same expiration time is set, when the expiration time arrives there will be peer-to-peer DB request wave after wave, such pressure wave will be passed to the next cycle and even appear superimposed.

The solution to go-zero is:

- Use distributed caching to prevent cache avalanches due to single point of failure

- Add a standard deviation of 5% to the expiration time, 5% is the empirical value of the p-value in the hypothesis test (interested readers can check for themselves)

Let's do an experiment, if we use 10,000 data and the expiration time is set to 1 hour and the standard deviation is set to 5%, then the expiration time will be more evenly distributed between 3400 and 3800 seconds. If our default expiration time is 7 days, then it will be evenly distributed within 16 hours with 7 days as the center point. This would be a good way to prevent the cache avalanche problem.

Cache Correctness

The original purpose of introducing cache is to reduce DB pressure and increase system stability, so we focus on the stability of the cache system at first. Once the stability is solved, we generally face the problem of data correctness, and may often encounter "why does it still show the old one when the data is obviously updated? This kind of problem. This is what we often call the "cache data consistency" problem, and we will carefully analyze the reasons for it and how to deal with it.

Common practices for data updates

First of all, we talk about data consistency on the premise that our DB update and cache deletion will not be treated as an atomic operation, because in a highly concurrent scenario, we can not introduce a distributed lock to bind the two as an atomic operation, if the binding will largely affect the concurrency performance, and increase the complexity of the system, so we will only pursue the ultimate consistency of data, and this article is only for non-pursuit of strong consistency requirements of highly concurrent scenarios, financial payments and other students judge for themselves.

There are two main categories of common data update methods, and the rest are basically variants of these two categories.

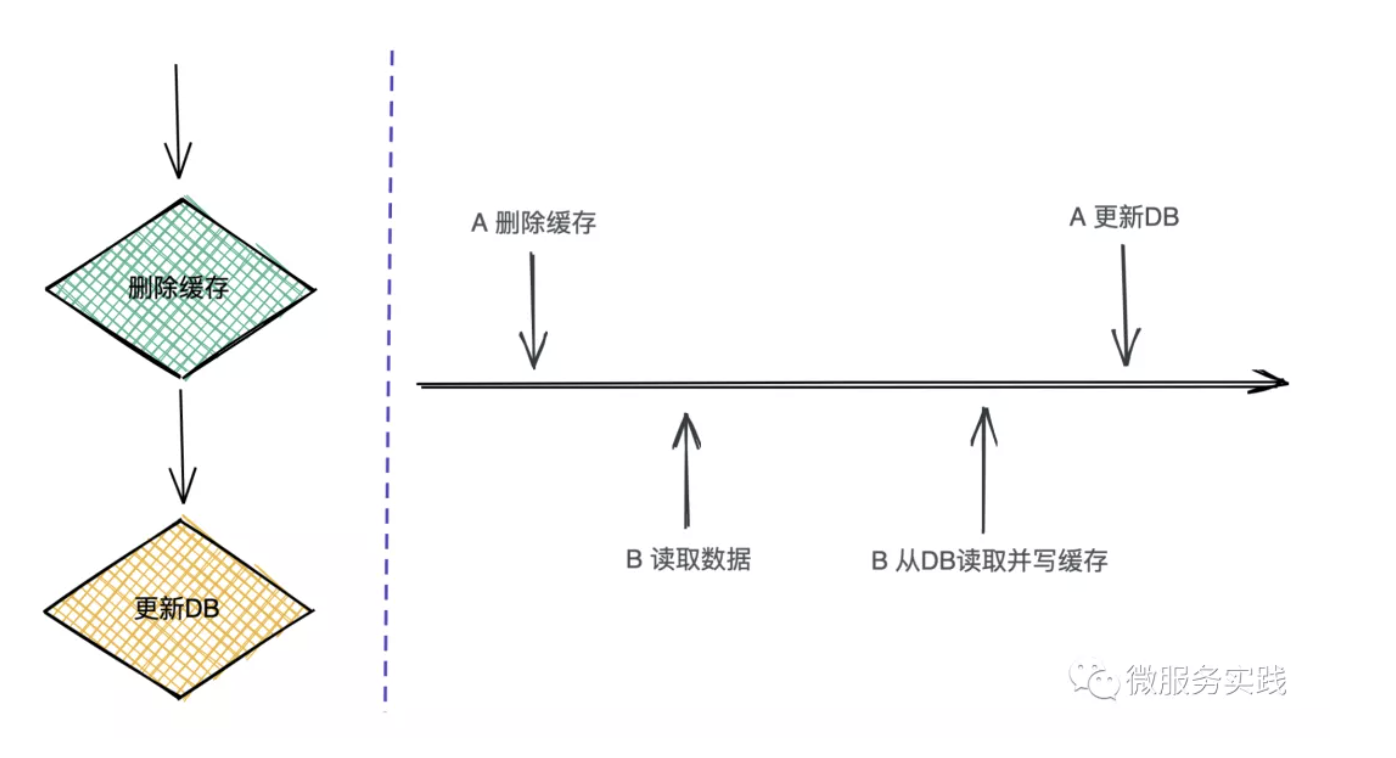

Delete the cache first, then update the database

This approach is to encounter a data update, we go to delete the cache first, and then go to update the DB, as shown in the figure on the left. Let's look at the flow of the whole operation.

- A request needs to update data, delete the corresponding cache first, not yet update DB

- B request to read the data

- B request to see no cache, go to read the DB and write the old data to the cache (dirty data)

- A request to update DB

You can see that request B writes dirty data to the cache. If this is a read more write less data, it is possible that the dirty data will exist for a longer period of time (either with subsequent updates or waiting for the cache to expire), which is not acceptable for business purposes.

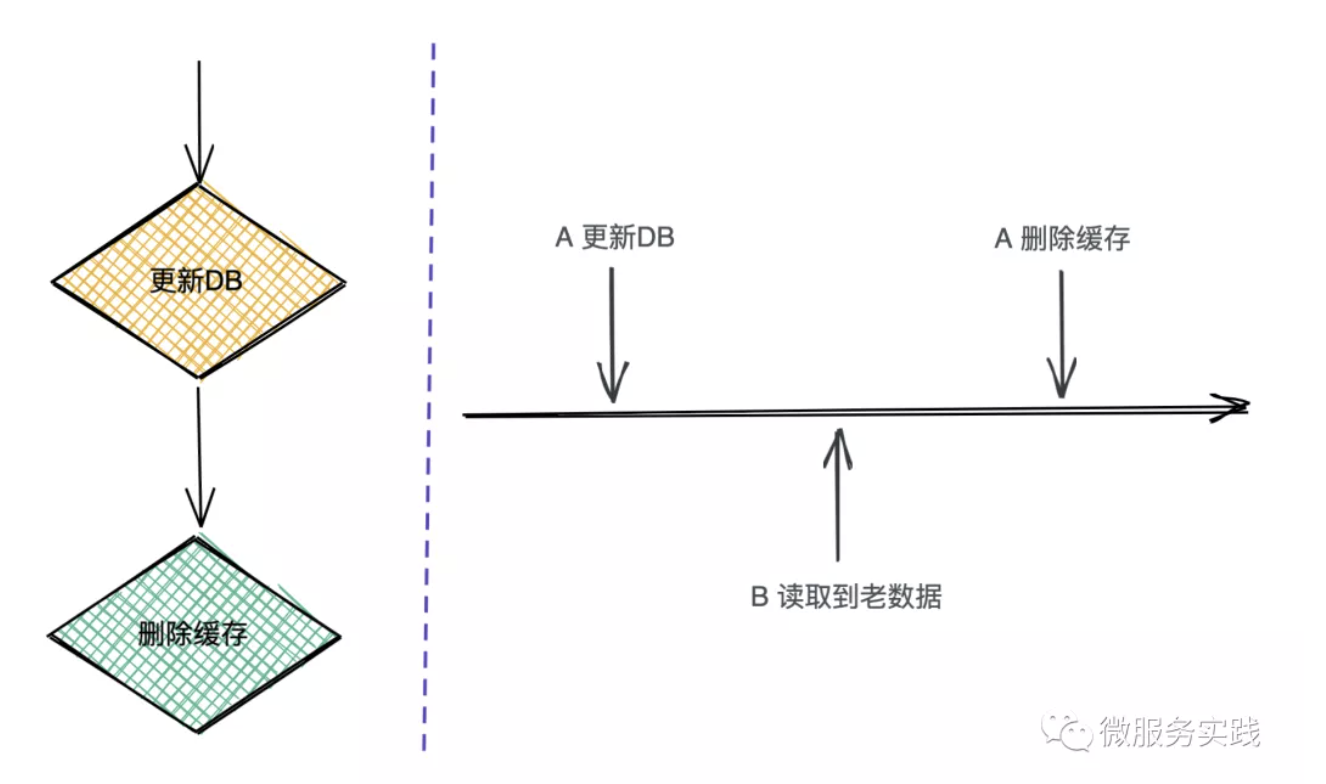

Update the database first, then delete the cache

The right part of the above figure can see that between A update DB and delete cache B request will read the old data, because at this time A operation is not completed, and this time to read the old data is very short, can meet the data final consistency requirements.

The above figure can see that we are using the delete cache instead of the update cache for the following reasons.

When we do a delete operation, it doesn't matter whether A or B deletes first, because subsequent read requests will load the latest data from the DB; but when we do an update operation on the cache, it will be sensitive to whether A updates the cache first or B updates the cache first, and if A updates later, then there will be dirty data in the cache again, so go-zero only uses the delete cache method.

Let's take a look at the complete request processing flow together

Note: Different colors represent different requests.

- Request 1 updates the DB

- Request 2 queries the same data and returns the old data, this short time to return the old data is acceptable to meet the final consistency

- Request 1 deletes the cache

- Request 3 does not have it in the cache when the request comes again, it queries the database and writes back to the cache before returning the result

- Subsequent requests will read the cache directly

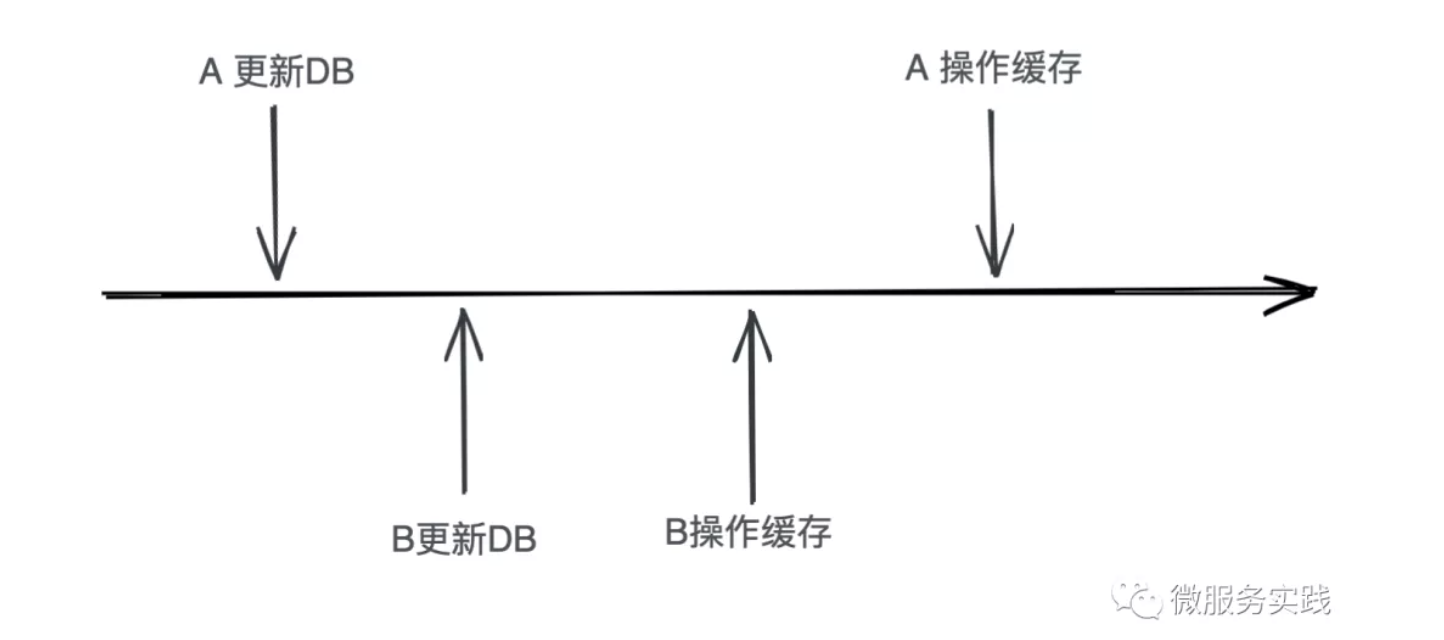

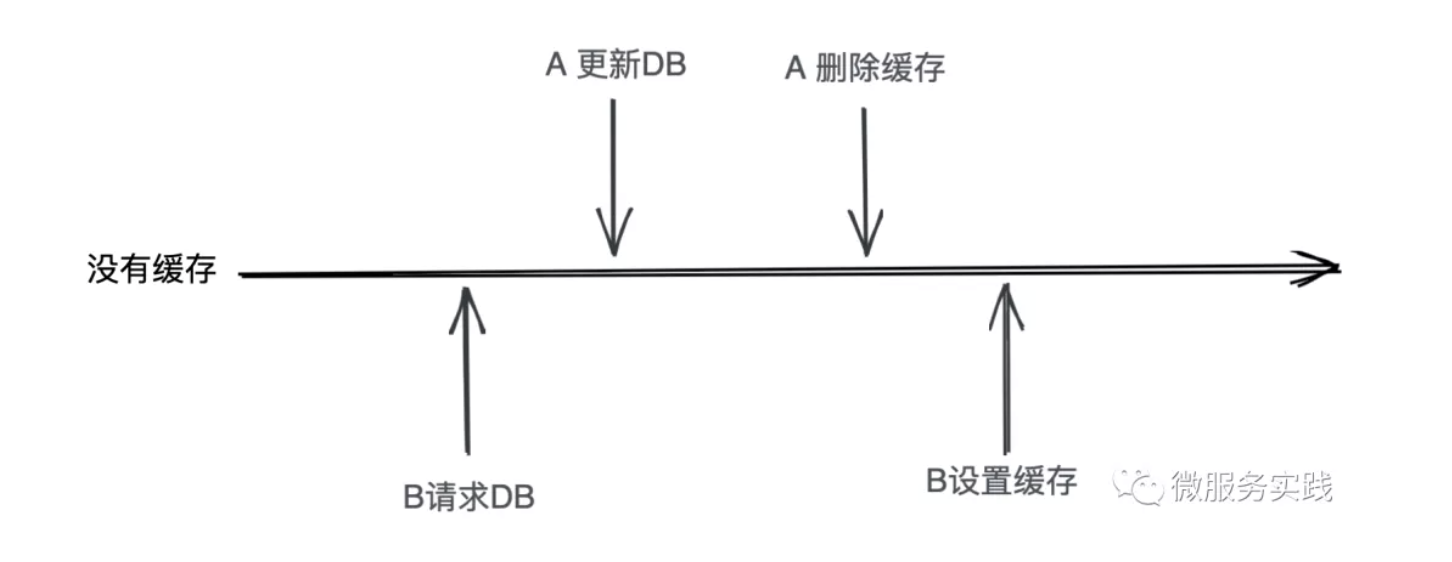

What should we do for the scenario below?

Let's analyze together several possible solutions to this problem.

Use distributed locks to make each update an atomic operation. This method is the least desirable, which is equivalent to self-defeating, giving up the ability of high concurrency to pursue strong consistency, do not forget that my previous article stressed that "this series of articles only for the non-pursuit of strong consistency requirements of high concurrency scenarios, financial payments and other students judge for themselves", so this solution we first give up.

Put A delete cache plus delay, for example, after 1 second before executing this operation. The bad thing about this is that in order to solve this very low probability, and let all the updates in 1 second can only get the old data. This approach is also not ideal and we don't want to use it.

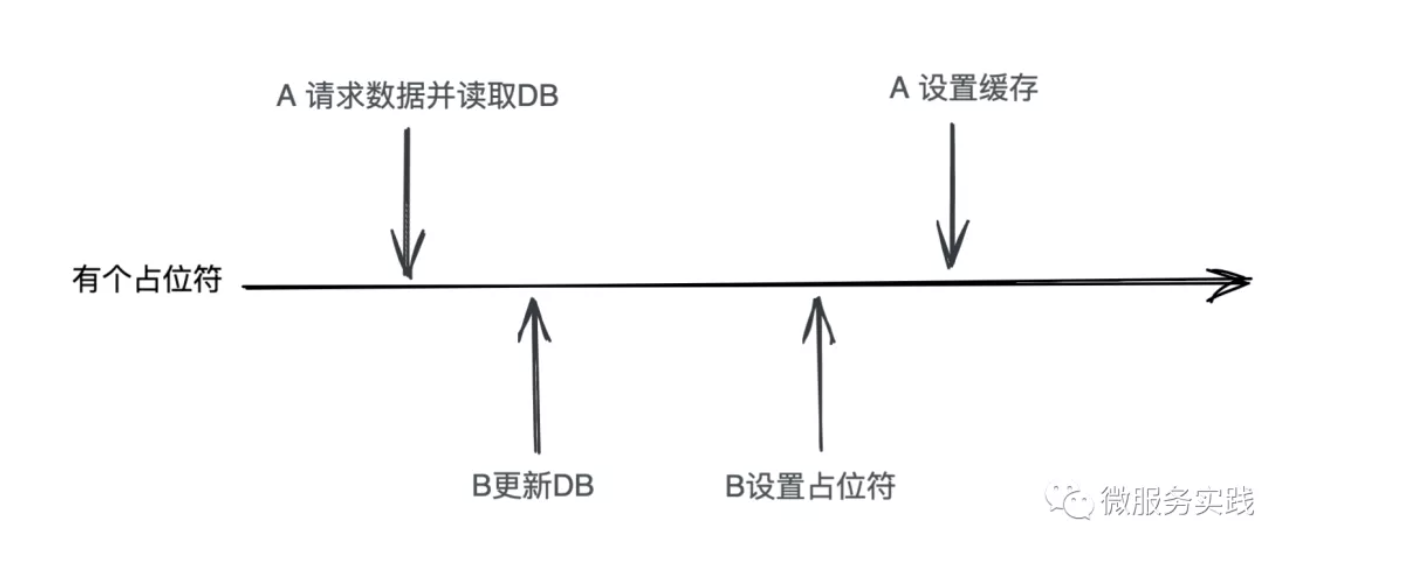

Change A to delete the cache here to set a special placeholder and have B set the cache using the redis setnx directive, then subsequent requests re-request the cache when they encounter this special placeholder. This approach is equivalent to adding a new state when deleting the cache, as we see in the following figure

Isn't it coming back around, because A request must force a cache or determine if the content is a placeholder when it encounters a placeholder. So this doesn't solve the problem either.

So let's see how go-zero reacts to this situation, and are we surprised that we choose not to handle this situation? So let's go back to the drawing board and analyze how this happens.

- The data for the read request is not cached (not loaded into the cache at all or the cache has been invalidated), triggering a DB read

- At this point comes an update operation on the data

- Need to meet this order: B request to read DB -> A request to write DB -> A request to delete cache -> B request to set cache

We all know that DB write operation needs to lock row records, which is a slow operation, while read operation does not need, so the probability of such situation is relatively low. And we have set the expiration time, the probability of encountering such a situation is extremely low in real scenarios, to really solve such problems, we need to ensure consistency through 2PC or Paxos protocol, I think this is not the method we want to use, too complicated!

The most difficult thing to do architecture I think is to know the trade-off (trade-off), to find the best balance of income is a very test of comprehensive ability.

Cache Observability

The first two articles we solved the problem of cache stability and data consistency, at this time our system has fully enjoyed the value brought by the cache, solving the problem of zero to one, then we have to consider how to further reduce the cost of use, determine which cache brings actual business value, which can be removed to reduce server costs, which cache I need to increase server resources, what is the qps of each cache, how many hits, whether there is a need for further tuning, etc.

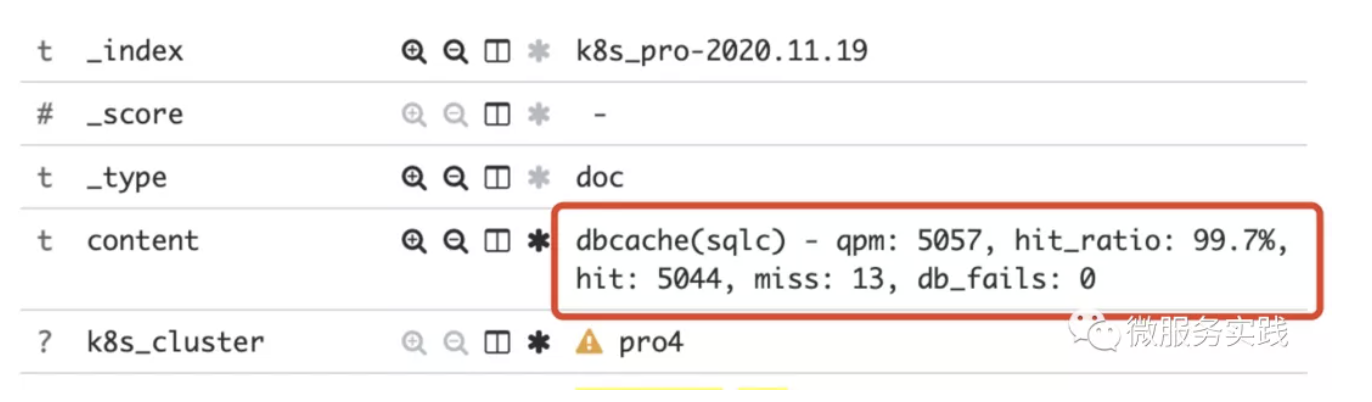

The above figure is the cache monitoring log of a service, we can see that this cache service has 5057 requests per minute, 99.7% of them hit the cache, only 13 of them fell to the DB, and the DB returned successfully. From this monitoring, we can see that this caching service reduces the pressure on DB by three orders of magnitude (90% hit is one order of magnitude, 99% hit is two orders of magnitude, and 99.7% is almost three orders of magnitude), so we can see that the benefits of this cache are quite good.

But if, on the other hand, the cache hit rate is only 0.3% then there is little gain, then we should remove this cache, one can reduce the complexity of the system (if not necessary, do not increase the entity well), the second is to reduce server costs.

If the qps of this service is particularly high (enough to put a lot of pressure on the DB), then if the cache hit rate is only 50%, which means we have reduced the pressure by half, we should consider increasing the expiration time to increase the cache hit rate according to the business situation.

If the qps of the service is particularly high (enough to put a lot of pressure on the cache) and the cache hit rate is also high, then we can consider increasing the qps that the cache can carry or adding in-process caching to reduce the pressure on the cache.

All of this is based on cache monitoring, and only when it is observable can we make further targeted tuning and simplification, and I always emphasize that "without metrics, there is no optimization".

How do I get the cache to be used in a regulated way?

For those who know go-zero design ideas or have watched my videos, you may have an impression of what I often say about 'tools over conventions and documentation'.

For caching, there is a lot of knowledge, and each person's cache code will be very different, and it is very hard to get all the knowledge right. So how does go-zero solve this problem?

- By encapsulating as much of the abstracted generic solution as possible into the framework. This way the whole cache control process doesn't need to be bothered with, as long as you call the right method, there's no chance of error.

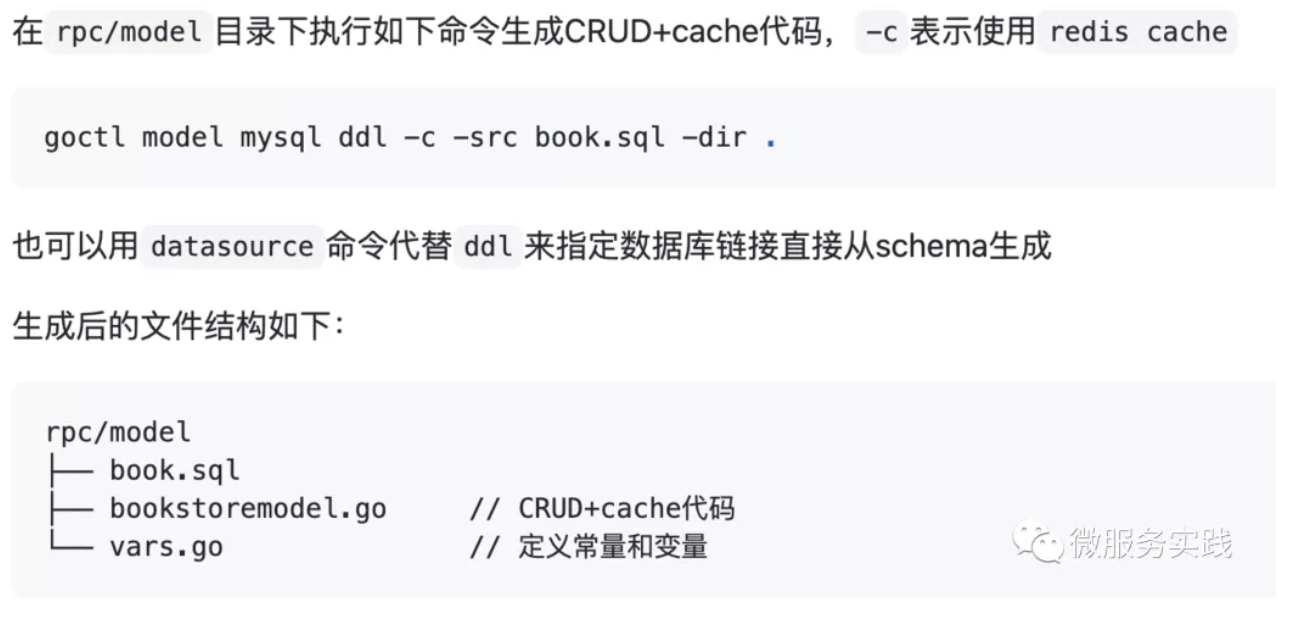

- The code from building the table sql to CRUD + Cache is generated by the tool in one click. It avoids the need to write a bunch of structure and control logic based on the table structure.

This is a CRUD + Cache generation description cut from go-zero's official example bookstore. We can provide schema to goctl with a specified table build sql file or datasource, and then goctl's model subcommand can generate the required CRUD + Cache code with one click.

This ensures that everyone writes the same cache code, can tool generation be any different?